version française:

Chapter 10

(translated from French)

From arranged marriage to passionate love:

on the destiny of an attribute of matrimonial exchange

in the story of Tristan

III - 10

Why has this formely ridiculous feeling of love almost become a respectable passion? asks Adam Smith. “Love that once represented a ridiculous passion has become more serious and respectable. As proof, none of the ancient tragedies had love as a motive, whereas nowadays it is considered respectable and the theme influences all public entertainment”. This metamorphosis from ridiculous to respectable forms the subject of the following paper.

*

Marriage brings together two specific concerns: the “natural” (in the sense that a biologist could write a “Natural history of marriage”) and the social. It imposes a harmony of appearances – eventually consent – being a matter of what ethology calls “pariade”, aiming at the reproduction of species, as well as a socio-economic harmony, aiming at reproducing patrimony. As family is the framework of this double reproduction, it is obvious that this passing of generations could be subject to the contradictory concerns of the two sides of reality.

“- She only has one eye! objects the fiancé of an arranged marriage in a light comedy.

- It’s true, but she has two millions!”

There, of course, exist rules to these arrangements where a dowry can boost the family fortunes or a phenotype a genealogy: the marriage has to be consummated (thus the minimum of physical requisites are needed) and it has to be lawful, the law defining the minimal distance of possible matrimonial unions.

A modern man, who is interested in traditional societies, is perplexed by the upsetting acknowledgement that the feature which seems to give life its spice – passionate love – appears worthless (which obviously does not deny its existence; it is perceived as a particular – and precarious – form of imprinting: according to traditional wisdom “in a marriage of love it is marriage that destroys love whereas in a marriage of reason, love springs from marriage”) if not bothersome or a fault likely to cheapen the seriousness of social arrangements.

In fact, in traditional societies marriages result from material considerations and from exchanges between families where futures are virtually bound before even seeing the light of day. “Whatever one might say, one does not marry for himself; one marries for as much or more for his descendants, for his family. The use and interest of marriage touches our race far above us. However, this way pleases me, that we conduct it rather by a third party than by our own and by the will of others rather than by one's own. All this, how many contrary of amorous conventions! Also is it a type of incest to go and employ to this venerable and sacred parenthood the efforts and extravagances of amorous licentiousness” (Essais, III, 5) (“On ne se marie pas pour soy, quoi qu’on die ; on se marie autant ou plus pour sa postérité, pour sa famille. L’usage et interest du mariage touche nostre race bien loing par delà nous. Pourtant me plait cette façon, qu’on le conduise plustost par mains tierces que par les propres, et par le sens d’autruy que par le sien. Tout cecy, combien à l’opposite des conventions amoureuses ! Aussy est ce une espece d’inceste d’aller employer à ce parentage venerable et sacré les efforts et les extravagances de la licence amoureuse.” - Essais, III, 5) By contrast we are happy to imagine that our feelings compose the principal element of our matrimonial arrangements. We well know, even if we didn’t want to and even without having read Alain Girard’s limpid essay entitled “Le choix du conjoint”, that in reality it's different. But this belief is anyhow inscribed on the pediment of our values and constitutes the primary motive of the largely western type of literature, the novel. That is to say that we [–...–] forgive this not very orthodox definition, the celebration of passionate choice (romantic love) in contrast to rational one. The novel being the epic of the individual who firstly frees himself from the family’s control of arranged marriages.

- “We” don’t want to know in fact. Under the title “Ah ! Sweet mistery!” Time magazine 24th of March 1975 quotes Senator William Proxmire opinion on awarding a psychologist of the Minnesota University a funding of $84,000 for a study on “why people fall in love”. “Even the National Science Foundation, the senator protests, can not claim that falling in love is a science. I believe that two million Americans prefer leaving certain things in life to Mystery. And at the top of those we don’t want to know about is why a man falls in love with a woman and vice versa. If even if they think they can give us an answer, we don’t want to know about it.” It is certainly not in our intentions to lop this mountain of convinced ingeniousness.

[The senator Proximire became famous for his “Golden Fleece Awards, battling against the governments wasteful spending – see The Fleecing of America, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1980 – and in particular attacking research projects. A scientist said that this fundamentalist of public spending – the senator himself involved in this excess – had nothing but bone between his ears”.]

- Two youngsters, unknown to each other, go to a hotel. Both had just spent time abroad (ERASMUS before its creation) to satisfy their families requests for an arranged marriage and together they came to agreement to protest against these barbarian customs. They fall in love, of course, against the plans of the families. A miracle: without knowing they are the partners of this arranged marriage. In this light comedy love appears as an individual sanction of social arrangements. The sequel of Ménandre’s comedy illustrating the validity and the triumph of the norm, plays on the same opposition, mutatis mutandis: love that governs the actions of its “victims” (Dyskolos, v. 347) and guides their steps (v. 545) reveals itself to be the architect of necessity. Matrimonial agencies which advertise themselves as “giving Fate a helping hand” in its choices, have some knowledge of the winning formula in question and on the reality of social arrangements.

- In fact, the form has its equivalent when the constitutional necessities are confronted with psychological uncertainties. For example the famous Monogatari, a masterpiece of Heian times, could be summarized as the story or a sanction of such a passion over three generations. The emperor is excessively attached to his “modest-ranking” wife. As the imperial marriage lays the foundations of the political and religious organisation of the whole kingdom, this passionate commitment in the institution is a source of trouble. Hikaru Genji, Prince of Light is the fruit of this “guilty” love, when love overrides ranks and blood ties. The emperor, broken down by the death of his favourite one, hears about a girl who strangely looks like his deceased wife. He marries her. Genji sets about charming this Lady Fujitsubo who is the living portrait of his mother (“Because so it was that he could not take his eyes off the empress”). A son is born of this union, Reizi, who is considered as the son of the emperor and thus succeeds to the throne – and abdicated, eaten away by the ambiguity of his birth…

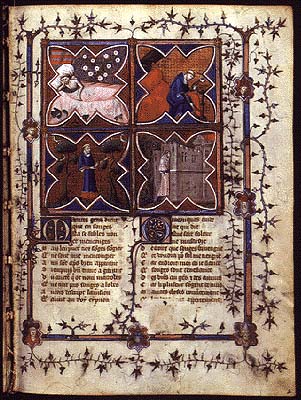

Copie du manuscrit du Genji Monogatari

(XVIe siècle)

Murasaki Shikibu : c. 978 - c. 1014

I propose to take a look at the story of Tristan and Isolde, by examining the matrimonial structure of the story that has been identified as the original scene for the Western novel; this critical, tragic, mortifying but yet thrillingly readable passage from imposed choice to freedom of choice, from arranged marriage to passionate love. Moreover, the story in question, Tristan’s love for the spouse he was to conquer for his maternal uncle is developed on this ethnologically relevant main theme of matrimonial structure, that is the uncle-nephew relationship and to which ethnological literature provides, in a population as symbolic to this disciple as the novel of Tristan could be to literary history – I mean to say the Dogons – an isomorphic solution to the rivalry between the uncle and the nephew. But we could say that this consideration is theatrical and literary, whereas a Western reader is persuaded, like the senator Proxmire that he “carries out” the novel.

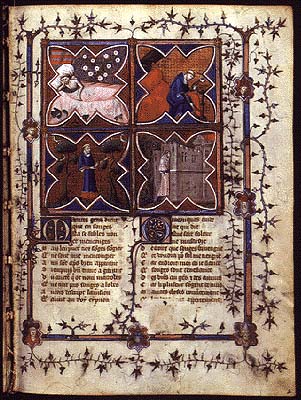

Bibliothèque Nationale de France

“Et comme ainsi tu es venu sur terre

par tristesse, tu auras nom Tristan.”

“And as by sadness you came to this world

your name shall be called Tristan.”

The story of Tristan et Isolde shows passionate love contradicting the rules of matrimonial exchange.

The childhood of Tristan

Tristan is the uterine nephew of the King of Cornwall. “Long ago, when Mark was King over Cornwall, Rivalen, King of Lyonesse, heard that Mark’s enemies waged war on him; so he crossed the sea to bring him aid; and so faithfully did he serve him with counsel and sword that Mark gave him his sister Blanchefleur, whom King Rivalen loved marvellously.” (Bédier, The Romance of Tristan and Iseult, as retold by Joseph Bédier, New York, Random House, 1965 : 3-4). Upon his return to Lyonesse, King Rivalen is killed by an act of treachery. Some days later, Blancheflor dies while giving birth to Rivalen’s son. “Little son, she says, I have longed a while to see you, and now I see the fairest thing ever a woman bore. In sadness came I hither, in sadness did I bring forth, and in sadness has your first feast day gone. And as by sadness you came to this world your name shall be called Tristan; that is the child of sadness”. (Bédier, 1965 : 4)

“When seven years were passed and the time had com to take the child from the women” (Ibid.: 5), Tristan is placed in the care of “a good master, the squire Gorvenal”. Whether by Tristan’s will: “For a long time I wanted to travel. I would notably prefer Cornwall, there where my father took his wife” (Mary, 1937 : 10), whether by fortuitous circumstances – he ignores where it is situated – the son of Blancheflor reaches King Mark’s land. The King becomes attached to the unknown child, “wondering whence came his tenderness, and his heart would answer him nothing; but, my lords, it was blood that spoke, and the love he had long since borne his sister Blanchefleur”. (Bédier, 1965 : 8)

The carbuncle

Thanks to a carbuncle Blancheflor got as a wedding gift long ago, Tristan is recognized. He is knighted by his uncle. After having re-conquered Loonois from his father’s murderers and abandoned his land for his adoptive father, Tristan declares to his subjects: “Now a free man has two things thoroughly his own, his body and his land. To Rohalt then, here, I will release my land […] but my body I give up to King Mark. I will leave this country, dear thought it be, and in Cornwall I will serve King Mark as my lord. (Ibid.: 11)

The Morholt of Ireland

Back in Mark’s court, Tristan finds the country in great sorrow. “The king of Ireland had manned a fleet to ravage Cornwall, should King Mark refuse, as he has refused these fifteen years, to pay a tibute his fathers had paid [tribute imposed as a consequence of an unfortunate war when Mark was only a child]. For know you, certain old treaties gave men of Ireland the right to levy on the men of Cornwall one year three hundred pounds of copper, another year three hundred pounds of fine silver, a third year three hundred pounds of gold. When came the fourth, they might take with three hundred youths and three hundred maidens, of fifteen years of age, drawn by lot among the Cornish folk. ” (Ibid.: 13) “Now that year this King had sent to Tintagel, to carry his summons, a giant knight; the Morholt, whose sister he had wed, and whom no man had yet been able to overcome. (Ibid.: 13) “For his height, the size of his limbs, his great stature, the width of his shoulders, the strength of his arms he could only be compared to Goliath of Ascalon.” (Mary: 16). None of the barons dared to fight Morholt, so monstrous was his strength. (“Weakling, do you court death? To what end would you tempt God ? That one thought: “Is it to becom serfs that I have ree$ared you my dear sons, and you, my dear duaghters, to become harlots? But my death would not save you.” “Still they were silent, and the Morholt resemble an awk shut in a cage with small birds: when he enters, all grow mute.” locked inside a birdcage with birds: when he enters all go dumb with fear”.) (Bédier, 1965 : 14)

The notch of the sword

Tristan takes up the challenge, fights Morholt and slays him. He says: “My lords of Ireland, Morholt fought well. See her, my sword is broken and a splinter of it stands fast in his head. Take you that steel, my lords: it is the tribute of Cornwall”. (ibid.: 16)

The marine streams

But wounded at the hip by Morholt's poisoned weapon, Tristan is close to death. He is laid in a boat without a helm and entrusts himself to the course of the waves. Currents take him towards Ireland where the sister of Morhold, Isolde the Fair, lives. “She alone, being skilled in philters, could save Tristan, but she alone whihesnhim dead. was the only one amongst the women who wanted him dead.” (ibid.: 18) Tristan lands on Ireland and takes the identity of a minstrel called Tantris. “After forty days, Iseut of the Golden Hair had all but healed him [...] he fled and he cam again before Mark the King. (ibid.: 58)

“King Mark had intent to grow old childless and to leave his land to Tristan” but his barons “pressed him to take to wife some king’s daughter who should give him an heir.” (ibid.: 20) “King Mark made a term with his barons and gave them forty days to hear his decision. On the appointed day he waited alone in his chamber and sadly mused: ‘Where shall I find a king's daughter so fair and yet so distant that I may feign to wish her my wife?’ Just then by his window that look upon the sea two building swallows came in quarelling together. Then, startled, they flew out..." (ibid.: 20).

The golden hair

“But had let fall from their beaks a woman's hair, long and fine, and shining like a beam of light. King Mark took it, and called his barons and Tristan and said:

– To please you, lords, I will take a wife; but you must seek her whom I have chosen [...] she whose hair this is; nor will I take another.”

Then the barons saw themselves mocked and cheated and they turned with sneers to Tristan for they thought him to have counselled the trick. But Tristan, when he had looked on the hair of gold, remembered Iseut the Fair [...]

– King Mark [...] I will go seek the lady with hair of gold [...] I would once more put my body and my life into peril for you.” (ibid.: 21)

When Tristan, disguised as a merchant arrives in Ireland, a monster besets the country. “Daily it leaves its den and stands at one of the gates of the city: Nor can any come out or go in till a maiden has been given up to it; and when it has in its claws it devours her in less time than it takes to say a Pater Noster."

Every day the beast comes down from its cavern and stops at one of the town gates. No one can leave nor enter the town before he is given a young girl; and, as soon as he has her in his claws, he devours her in a time shorter than needed to pronounce an Our Father (Ibid., 64). “The King of Ireland proclaims by a herald that he will give his daughter, Iseut the Fair, to whomsoever shall kill the beast.” (ibid.: 23-22) Tristan slays the beast but collapses, poisoned by his venomous breath. Once more, the queen takes care of Tristan and heals him. But one day, she examines his weapons while Tristan is sleeping and notices the blade of his sword. She remembers the splinter of steel lodged in her brother Morholt’s head and notes that it fits perfectly in Tristan’s sword. She immediately conceives a plan to kill her brother’s murderer, in whom she recognizes Mark’s nephew, also known as Tantris. Tristan reveals that he came to win his daughter for his uncle, King Mark of Cornwall, and tells the story of the swallows. “See here, amid the threads of gold upon my coat [the] hair is sown: the threads are tarnished, but [the] bright hair still shines.” (ibid.: 27) “By this marriage… people of Ireland and Cornwall will be friends and allies for ever.” (Mary: 51).

*

Therefore, here are the classic traits defining the values of education and the forms of marriage. Rivalen, King of Loonois, made an alliance with Mark, King of Cornwall, and married his sister. Tristan, having received his instructions (“When came the time to take him back from women”), “instinctively” attracted by his maternal kin (he arrives, “by accident” at his uncle’s court, who is taken with affection for him without having recognised him) or institutionally taken care of by it, achieves his initiation into his maternal uncle’s court. Knighted by him, he delivers the Kingdom of Cornwall from a human tribute, after a remarkable combat against a monstrous foreigner. Poisoned by the monster’s venom and perilously close to death, Tristan finds a cure in the monster’s sister, Isolde, the bride of Gormont, King of Ireland. This exploit entitles Tristan to marry. But, as the uterine nephew of Mark, Tristan occupies a matrimonial go-between position towards the court of Cornwall and the court of Lyonesse. As Rivalen married Blancheflor, Mark’s sister, we could consider that his kinship acquits him from a debt of spouse thanks to the matrimonial quest that Tristan undertakes for his uncle’s benefit. The golden hair that makes Mark decide to take a wife is the golden thread of the alliance that weaves the web of matrimonial arrangements between the families. Having conquered the monster of Ireland, won the daughter of the king for his uncle, Tristan, although recognised for having murdered Morholt, puts an end to the hostility between Ireland and Cornwall – thanks to this murder and marriage – and at the same time, extinguishes the debt of his kin.

At the base of these common rules, the theme of the novel of Tristan consists in transgressing the direction of the matrimonial exchange: Tristan falls in love with the woman that he is charged with giving back to his uncle – and specifically of the principle that supports its exercise. Passionate love is this fatal relationship that carries off two beings for whom matrimonial rules forbids the union.

What is the nature of the attachment between Tristan and Isolde? What makes the story of Tristan valuable, amongst other things, is, precisely, that passionate love seems to be like a perversion of the institutional structure, a perversion that reveals the function of this structure. What determines masculinity is not only separation from the mother, dramatised in the initiation, this being accomplished in reality by the separation of the sister and in the fulfilment of the matrimonial exchanges. By shirking the rules of the exchange, the brother is kept in the security of an innermost existence. “Everyone has his story” as Gombrowicz would say (infra: chapter 11) in his metaphysic. Tristan’s love for Isolde cancels out the victory over the monster. Of course the love potion plays an essential role in the novel and it’s an error that is fatal to the two heroes.

The philter

Whilst Tristan was taking an oath before Gormont to lead Isolde loyally to her Lord, “Iseult the Fair trembled for shame and anguish. Thus Tristan, having won her, disdained her; the fine story of the hair of gold was but a lie; it was to another he was delivering her... But the King placed Iseult’s right hand into Tristan’s right hand, and Tristan held it for a space for token of seizing for the King of Cornwall. So, for the love of King Mark, did Tristan by guile and by force conquer the Queen of the Hair of Gold.” (Bédier, 1965: 30)

“When the day of Iseult's livery to the lords of Cornwall drew near, her mother gathered herbs and flowers and roots and steeped them in wine, and brewed a potion of might, and having perfected it by science and magic, she poured it into a pitcher, and said apart to Brangien:

– Girl, it is yours to go with Iseult to King Mark's country, for you love her with a faithful love. Take then this pitcher and remember well my words. Hide it so that no eye shall see nor no lip go near it: but when the wedding-night has come and that moment in which the wedded are left alone, pour this essenced wine into a cup and offer it to King Mark and to Iseult his Queen. Oh! Take all care, my child, that they alone shall taste this brew. For this is its power: they who drink of it together love each other with their every single sense and with their every thought, forever, in life and in death.” (31-32)

During the voyage, Isolde’s heart felt heavy with hatred and spite for the murderer of her uncle who was now carrying her off to an enemy land.

“The sun had entered the sign of the Crayfish. It was the Eve of St John. From the hour of the third prayer, the heat rose on the sea and by the afternoon there was such heat in the air that sailors, knights, men and women were lying down and sleeping because they felt so wrought and exhausted.” (Mary: 58) “Tristan came near the Queen to calm her sorrow. The sun was hot above them and they were athirst and, as they called, [a little maid] looked about for drink for them for them and found that pithcher which the mother of Iseult had given into Brangien's keeping. And when she came on it, the child cried: “I have found you wine!” she cried. Now she had found not wine – but Passion and Joy most sharp, and Anguish without end, and Death.

The child filled a goblet and presented it to her mistress. The Queen drank deep of that draught and gave it to Tristan and he drank also long and emptied it all. Brangien came in upon them; she saw them gazing at each other in silence as though ravished and apart [...]

“Iseult, my friend, and Tristan, you, you have drunk death together.”

“And once more the bark ran free for Tintagel. But it seemed to Tristan as though an ardent briar, sharp-torned but with flower most sweet smelling drave roots into his blood and laced the lovely body of Iseult all round about it and bound it to his own and to his every thouht and desire.

Once again, the ship headed for Tintagel. It seemed to Tristan that a hardy bramble bush, with needle-sharp spines and sweet-smelling flowers was growing roots in the blood of his heart and with strong links was entwining his body and all his thoughts and desires to Isolde’s beautiful body.

“Iseult loved him, though she would have hate. had he not disdained her? She could not hate, for a tenderness more sharp than hatred tore her.

“She wanted to hate him but couldn’t; irritated in her heart by this tenderness that was more painful than hatred.” (Bédier, 1965: 34) They searched for each other “as blind men seek, wretched apart and together more wretched still, for then they trembled each for the first avowal. (ibid.: 34) When their eyes that had fled one another, met in a flash, a perilous look fanned the flame that had already consumed them. Each of them struggled inside. Both Reason and Desire delivered a cruel battle. The Maiden wears natural shame as her shield; faith and honour both uphold and torment the young man. After the dangerous first sight comes the moment to touch, then to bestow her, and finally the the defended act which diverts the look of God and withdraws the esteem of men.” (Mary : 59)

“On the third day, as Tristan neared the tent erected on deck where Iseult sat, she saw him coming and she said to him, very humbly :

– Come in, my lord.

– Queen, said Tristan, why do you call me Lord? Am I not your liege and vassal, to revere and serve and cherish you as my lady and Queen ?

But Iseult answered:

– No, you know that you are my lord and master, and your slave!” [...]

Regretting her happy childhood…

– ...But then I did not know what now I know.

– And what is it that you know, Iseult? What is it that torments you?

– Ah, all that I know torments me, and all that I see. This sky and this sea torment me, and my body and my life.

She laid her arm upon Tristan's shoulder, the light of her eyes was drowned and her lips trembled.

Her repeated :

– Friend, what is it that torments you ?

– The love of you, she said. [...]

The lovers held each other; life and desire trembled through their youth, and Tristan said :

– Well then, come Death.” (Bédier, 1965: 34-35)

Amorous passion, this guilty weakness, so strong, so pathetic and so close in the pages that we’ve just read, cannot exist in a heart as noble as Tristan’s. It’s a tragic mistake that’s at stake. This mistake however, highlights a necessary opposition: here, confusion, between the role of an individual, (a nephew) as intermediary and representative between two groups, maintaining matrimonial relations and one’s own ‘private’ interests; a psychological and social position, when he is taken in a system of exchange that defines his part – a part for which he can make no exception. In elsewhere, they say and we will see, whilst the ritual attitude of a nephew for his uncle is explained by an incestuous pursuit of the mother, the uncle has a debt towards his nephew, a debt which he frees himself from by giving him the hand of one of his daughter in marriage. Everything happens as if Tristan “was claiming” as a wife, the woman that his relatives “owe” to his maternal uncle. Confusion is provoked by the development of the exchange structure. Tristan wins the princess for his uncle and she (in turn) does not know that he is the champion of another; it’s during the voyage to Tintagel, in the dangerous closeness of youth that the fatal imprinting takes place.

Whilst, amongst the Dogon’s, this possibility of a union between a nephew and the wife of his maternal uncle is parodically diverted by what we call “joke relationships”, in here it would be its literary and tragic manifestation. Passionate-love would be this special form of relationship between the sexes, engaged in a proximity that ends, paradoxically, not in sexual reproduction, but in the death of the partners. Thomas Aquinas argued that marriage under the same roof, if it was permitted, would not fail to unleash passion...(Somme, 2a 2ae, 154.9) It is perhaps worthwhile mentioning that in Ancient Egypt, where marriages between brothers and sisters were legal (infra: chapter 13), also developed an amorous literature, exchanged, precisely, between close partners. The Mohave Indians observe a specific rite during a marriage between cousins or blood relations (though such a marriage is exceptional.) A horse belonging to the fiancée’s family is sacrificed. It represents the fiancé and its slaughter represents the dissolution of the blood lines between the spouses. It’s the only marriage for which the society forbids the divorce, it’s an illegal, immoral and dangerous marriage for the spouses and their “lineage.” It is accompanied by romantic love in the Western sense. It finishes, in general, like sexual relations with shadows, by an early death.” (Devereux, 1965: 239)

It is not love, as the form of matrimonial attachment, that is blamed, but it’s accursed face, passionate love. “[Because] without love, the rich palaces and the gold of Midas would never be worth, with love, the woodcutter’s hut and the shepherd’s bowl" (Mary : 5).

Here is a dialogue between Tristan and Isolde during the voyage.

“– Sir Tristan, love and lordship rarely go together well. Would it not be better to be of small status, to be poor in cloth and in fortune and to be joyful, that be high-ranking with sadness and pain? You said that to me yourself once.

– Honest woman, that’s the pure truth. But can’t love reside in beautiful chambers painted like in a small country cottage?” (Mary : 57) Cured the first time by the Queen of Ireland’s magic, Tristan, to justify his departure, gave as an excuse a matrimonial situation in which love, against all expectation, is allied with duty: He loves a cantankerous and greedy wife who does not care for him:

– I’ll tell you, the Queen, I’ve married a villain who ruins me and horribly grumbles when I don’t bring any money. She likes Dan Denier better that rhymes and less the sound of the harp than cabbages and porridge.

– You love her nevertheless, Tantris, since you chose her! She must indeed have some merits?

– Will we ever know, Queen? Maybe I’m like someone who has an ugly duckling frowning like a monkey for a lady and yet doesn’t stop calling her a rose in full bloom and defies anyone who doesn’t declare her to be the most beautiful. Love can make us that insane.

The potion that the Queen meant for Mark and Isolde is to implement this imprint between the spouses, to provoke an improbable love between two people who don’t know one another, and whilst Isolde’s heart is already taken.

Tristan’s morale proceeds from this “description of reckless joy and great excess of love that drag his conquests from one distress to another, right until his painful exit from this transitory world. (Ibid.: 5) The love that he feels is a sacrificial passion: Tristan, “loyal and authentic… is resigned like a true martyr to the God of Love;” Isolde “ described in her exhiliration and her sadness, carried away into the same fatal cycle as the swallow that the sparrowhawk drives to death, having not betrayed his natural rights as Lord that under his empire of unlimited strength, as black magic that overcomes and annihilates his honest will. (Mary:5) This “strange love that injures four people, each one suffers and is afflicted because of it, and all live in a sadness without finding joy. (Fragment de Turin). This “marvel” [on the value of “marvel” see: “Qui son droit seignor mesconcencelle/Ne puet faire greignor mervelle.” – Béroul: 2516-2517]:

“J’am Iseut a mervelle

“Si que n’en dor ne se somelle.” (Béroul : 1375-1376)

cette “folie”:

“Amors par force vos demeine !

“Combien dura vostre folie

“Trop avez mene ceste vie... (Béroul : 2270 s.)

est exemplaire par la qualité de ses victimes, et n’est pensable que par une cause extérieure au cœur des amants :

“...por Deu omnipotent,

“Il ne m’aime pas ne je lui

“Fors par un herbé dont je bui

“Et il en but : ce fut pechiez.” ( Béroul : 1386 s. )

*

Among the Dogons (but in other African societies as well), the nephew is singularised by an apparently anomic behaviour towards his uncle: wasting his goods and launching pleasantries of a sexual nature at his wife. According to Marcel Griaule (1954), the Dogons explain the ritual behaviour of the nephew towards his maternal relatives and, in particular, the “risqued jokes and [the] insults directed to the wife of his uncle” (36) by a pursuit of the mother. “He makes do with a sort of shadow of his mother, in other words, the wife of his uncle, who, furthermore, cannot have sexual relations with him. The difficulty is resolved by insults accompanied by thefts that constitute both taking possession of a cause for impunity since it simulates incest, and a catharsis.” (41).

We can see more generally in this attitude the liberation of tension particular to the exchange system, a double compensation that counterbalances the “disequilibria” of the exchange, both on the debt of the father and on the credit of the uncle: in societies where the son-in-law is the debtor never clear of his father-in-law, his son, in the next generation is the beggar who never tires of the brother of his mother and in this exchange where the uncle marries thanks to the matrimonial compensation received for the sister, the nephew poses as an untimely creditor of an account that’s already been settled. Reversing for his benefit, in a parodical way, the alliance from whence he proceeds, the nephew, “alone against all” Griaule says, grants to see the precedence of individual truth with regards to the social contract, of sentimental credit on the matrimonial debt, of passion on the rule. This is also what emerges from the Thonga system (Junod, 1936: 228-229), where the acquired wife, thanks to the matrimonial compensation of the sister of a man becomes identified with a mother by the husband of this sister and where the son of the latter is authorised to joke with this wife, towards whom his father his held in the highest respect and can, when his uncle dies, claim from him the matrimonial property. To the extent that the ban that sanctions the mans relations with this woman, acquired thanks to his own cattle marks the direction of the exchange, the cattle circulating in an inverse direction to the women, the nephew’s apparently incongruous privilege seems to be like a parodical calling off the marriage contract (reminding us furthermore by this pleasant denial the incontestable reality of the exchanged: we have an immediate definition of the protagonists when this type of behaviour is revoked) like the liberty granted to the subjects, not only to contest in a mocking way the contracts in which they are engaged, but to dream of an impossible return to the lost closeness or to the event of a close marriage. “The opposite of laughter is not seriousness, it is reality." At the heart of the exchange, like at the heart of identity, is the conscious of a necessary individual mourning in order to exist.

*

Is it indeed a counter-model that is put forward to the listener “a salutary lesson, as Thomas says, against all love’s traps” (v. 3143)? The destiny of the Book of Tristan in the Western tradition allows us to see that another reading of it is possible. This exemplary exception is also an exemplary precedent. The identification with the heroes engages us in a dramatic experience that, paradoxically, can serve as a model, which poses the question of whether this love burn, if it is fatal, can be desirable. The story of Tristan reveals the opposition between the fatalness of a destiny marked with sadness, because it is fixed in a sterile scheme and the norm of a fulfilled marital destiny. In order for this case to be evocative or simply intelligible, it needs to meet a disposition in the mind of the reader or the listener. In the system where moral and matrimonial destiny is accomplished by the assistance of an education that is fulfilled in the marriage exchange, the scenario personified by Tristan and Isolde is indeed an antitype, but this recognition supposes the existence of two contradictory evaluations, an identification, then a rejection, recognition and conspiracy of inner motions of the norm of the exchange. But what happens when the spouse is not “already there,” when the idiom and the requisits of the relationship become less important? “Nature is not foolish enough, states the Book of the Rose, if we gave it a good thought, to create Mariette only for Bobichon or Bobichon for Mariette, or for Agnes or for Perrette, but she has made all men for all women and all women for all men, each man communes with each woman and each woman communes with each man.”

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, The Book of the Rose, Parisian School, mid 14th century.

On the background of this natural “indifference” – an indifference at least as opposed to what we call “preferential marriage”; the liberty of indifference that opens the path to a liberty of preference – the mythology of love could be presented as a theory of the bringing together of the sexes and a theory of marriage prospering naturally in a situation of escheat from the traditional norm. The literary tradition of passionate-love can thus be analysed as the reformulation of a matrimonial model. Firstly, the “other” of marriage – “Marriage and love are two foreign lands” said Ermengard, countess of Narbonne – it infers another type of marriage. In The Princess of Cleves, Mr de Cleves portrays, at the cost of his life, the first character of a husband-lover – who was scoffed by his time (by Valincour’s pen in his Letters to the Marquise on the subject of the Princess of Cleves) “adultery by passion for his own wife.”

(Communication presented to the conference “Marriage-Marriages,” Luxembourg Palace - Jean Monnet University, Sceaux, May 1997.)

|

|

|